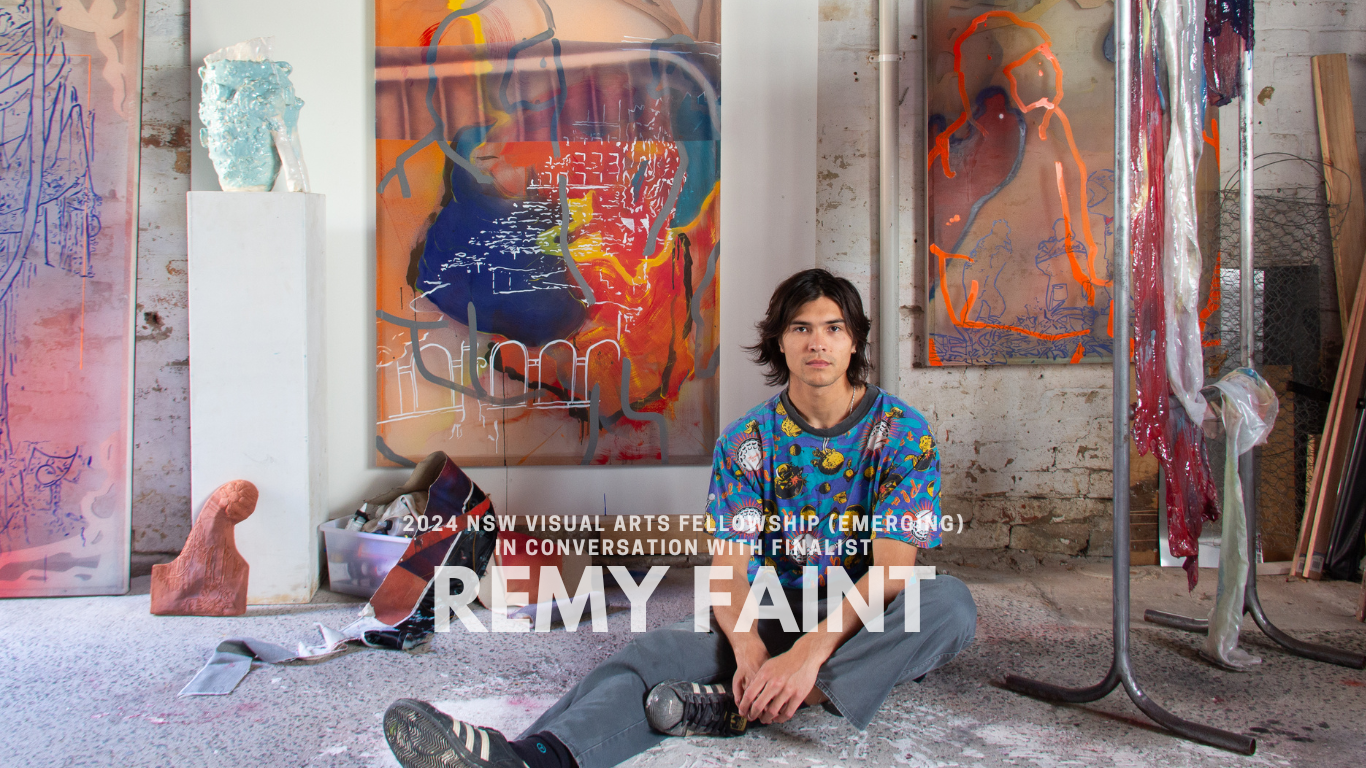

Remy Faint is an emerging artist celebrated for referencing collection-based objects and materials specific to his Chinese heritage within his art-making. As a finalist of the prestigious 2024 NSW Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging), Remy chats with Maeve Sullivan for Killdeers Magazine to discuss his practice, which mediates cross-cultural and material frameworks. It is his most ambitious exhibition to date.

Maeve Sullivan: What drew you to apply for the NSW Visual Arts Fellowship (Emerging)?

Remy Faint: The Fellowship has been such a significant opportunity for emerging artists for a long time now, and is something that has always been on my radar as an achievement or recognition. Many significant artists that I admire have been a part of the varying iterations over the years, and being able to engage with an arts organisation like Artspace is so beneficial in learning how these larger organisations work with artists, and vice-versa. The Fellowship itself is targeted towards professional development. I think a lot of people see the exhibition and think it’s just an art award – the exhibition is an outcome as part of the Fellowship, but it primarily focuses on your ability to develop a project, whether that's travel, residencies or mentorships etc. that will help your career.

MS: Do you think residencies are the most important thing for emerging artists to expand their practice?

RF: It depends on the residency. I’ve never done one overseas, but I’ve done one at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. It depends on your intention and how you use the residency. I know some people’s practice would find residencies quite beneficial, especially if their practice is site-specific. I wouldn’t say they are completely vital for everyone, but can offer a lot of creative time and freedom – it's not every day you get to dedicate a period of time to make art, especially in the reality of navigating a career in the arts. They're definitely a nice thing to do but for some artists, residencies might be more crucial early in their careers when they have the luxury of time. As artists get busier (with their career and life), finding time for something like a month-long residency might get harder. So, it’s good to take advantage of these opportunities early on.

MS: After graduating, what key lessons have you learned to help you succeed as a practising artist?

RF: I finished my honours in 2021 and just started an MFA. I completed my undergrad about three years ago. It’s been nice to have things going on afterwards because sometimes you need to be a little strategic. Some things in the art world are planned far ahead, while others pop up at the last minute. It’s good to always be making work, not just for long-term plans but also for unexpected opportunities that you can throw something in for like a group show. This consistency in working also is good for formulating and developing ideas. I found even post-uni, having a lot of documentation of works, whether or not they were in an exhibition, is important.

MS: Is Instagram your go-to for documenting works?

RF: Honestly yeah, nowadays, applications for shows or prizes are all online, and they look at images of your work. Instagram is probably almost equally as important to a website, if not more sometimes. It’s easier for people to look at someone’s Instagram rather than a website. Not everyone’s into Instagram, but it can be key.

MS: I saw you posted a photograph of your great-great-grandmother from Guangzhou, China circa the late 19th century on your Instagram. As you actively reflect and appreciate these memories, did you have any key childhood experiences that introduced you to the arts?

RF: That’s a good question because it ties very much into the initial kinds of things I made early on that feature within the fellowship. My Chinese side of the family immigrated to Australia in the late 1800s, so they came out here for gold mining but through discrimination relocated from the Victorian Goldfields and ended up in Tasmania for tin mining. We’ve always had significant objects such as clothing, fabric and textiles within my family that now function as heirlooms and have been kept. A lot of items ended up in a QVMAG museum collection in Launceston because they are deemed to be important signifiers of Chinese immigration in that area. Early on, we’ve always had these beautiful forms of textiles and prints and because my grandmother came from a silk-farming family in China, they have always been prevalent. This informed my interest in cultural craft. It was also an interesting way of figuring out different things about my history and ways of making through an art context. I wouldn't say this inspired me to make art, but it is definitely something I am interested in for its broader context.

MS: Would you say that the silk thread that metaphorically runs throughout your practice and your use of silk screens connotes something greater?

RF: If you look at it and zoom out, silk has been historically significant throughout global migration and cultural exchange. You look at the Silk Road and how that influences so many cultures. It has this larger historical connotation where you can look at how this material started in one place but was then translated and ended up in Europe. That links to my interest in looking at collection-based objects because to find specific historical silk-based painting examples, you have to look into museum collections. But I am also trying to create works that are genuine to me. I don’t want to just try to start making these silk paintings that ‘look’ like they’re trying to emulate these historical works. It’s not just replicating but using the materials creatively.

MS: VAF(E) provided me with a one-line bio of your practice, and it must be difficult to condense your entire art-making process and intention into a single sentence. The bio states: “You expand the languages of painterly abstraction by examining its global histories.” How would you begin to unpack that statement?

RF: I guess when considering different forms of communicating ideas, that’s why people choose art, like myself. To briefly unpack, it stems from my interest in painting and materiality, especially since uni. I’ve always been attracted to painting and different kinds of materiality to do with colour, tone, and texture, through a painterly lens. I say I am a painting artist, but I do other things as well, especially considering my practice includes a loose, gestural kind of mark-making, sculptural works, installation and ceramics. In education generally, a specific kind of history of painting is elaborated. It sounds cliche, but it obviously comes through a specific lineage or canon of art such as abstraction going back to Kandinsky, Modernism etc. I’m interested in how these Eurocentric histories intersect with my cultural heritage, which is Chinese. East Asian or Asian art practices often mirror ideas explored in Western modernist painting but are usually seen as secondary or adjacent to it. I’m not trying to critique this but rather shift focus to a different lens of looking at these forms of making.

MS: This abstraction created through spatiality seems to be central to your practice. It makes me think of your work included in The Tea Exchange, which was a collaboration between The Chinese Garden of Friendship and MOCA which you recently took part in. You mentioned how it was not the tea itself, but the specific metal tea boxes that evoke the aroma and smell of tea, that transport you. Do your works act as a portal? Are they biographical in that sense?

RF: Yeah, I mean it is, but I don’t want it to be objectively seen as just my identity. It’s a representation, but every work is an extension of oneself. I’m open to interpretations. The biographical aspect is in the materials I use, not necessarily in painting a portrait of my ancestors. It’s an exploration of ideas related to my biography but in a broader context.

MS: Would you say then your practice is spontaneous, do you have a planned end product or rather, or do the materials lead the way?

RF: It’s a bit of all of the above. I have an idea of the type of work I want to make, whether it's going to be a stretched painting, like the ones you see in the Fellowship exhibit, or if it’s going to be some kind of looser, assemblage work. The works are strategic in the sense that my process is quite rooted in layering. I keep old paintings, materials and fabrics in an archive that I’m open to reusing in new works. To me, it seems structured but to others, it may appear spontaneous. That’s where this creativity comes in, like when you are trying to solve a puzzle and it doesn’t seem finished. The whole art-making experience is a journey like this for me.

MS: I feel the same with writing, you can start with a vague understanding of where it ends but it’s worthwhile being open to the creative process.

RF: I feel like editing is where the magic of creativity happens. Because you know like anyone can make a good painting but it’s about trying to find the places to push and pull between, to challenge how it will be perceived in the end and maybe do something that isn’t obvious or is exciting.

MS: Anyone can make a painting, but not anyone can have that depth of knowledge or research to back it like yourself.

RF: That’s why it’s always funny when someone asks me how long it takes for me to make an artwork. I never know if they're asking about that in a physical sense or about the whole process from start to finish. I feel like it ends up taking a long time—it’s taken years in all honesty.

MS: It’s taken years, but this has been recognised and rewarded. This year you exhibited at A Single Piece, a contemporary art space in Surry Hills that subverts the traditional gallery model to create an immersive art experience and promote the work of artists of Asian heritage. How important was that space for you to showcase your art?

RF: The nature of the space is like an old kind of tailoring shop, and they have this big shop front window with space inside. They prioritise artwork to sit in the front window, lit up and viewable 24/7. The director Rose, and her partner Damian created the concept that also utilises an inside gallery space that can be used for a variety of purposes. I met them when they bought a work of mine a few years ago. That’s how I connected with them. It’s a good concept, especially for those who are not professional gallerists or are early in their careers.

MS: Your signature silk-based painting approach was on full display, including the work He Turned and Bowed, which is imagined as a window or a passageway into new perceptions, a semi-transparent threshold. So, as an emerging artist, what does it mean for this shopfront gallery to feature such a meaningful work of yours and make it accessible 24/7 to the public?

RF: Being able to promote your work is always good, especially in a place like Surry Hills, a busy area and its proximity to other galleries. Having your work physically accessible and viewable to people who might not necessarily walk into a gallery on their own accord is a great idea, as seeing something in the window can encourage them to go and explore either my work or even their own creative endeavours.

MS: This question is just out of curiosity. I’ve noticed there are lots of ladders emerging in your works lately, including at your exhibition at Cement Fondu. Is there a reason for that?

RF: In that exhibition, I was looking at a specific collection object called ‘The Library Cave’, a cave complex with many significant silk-based artefacts. It’s a notable point along the Silk Road. With the ladders, I wanted to expand upon these ideas of painting stretches and include something that alluded that you could climb in or out of the space. It was also used as a painting structure, allowing a narrative to unfold. It’s just a piece of wood and it extends into the things I am making now. I use a lot of structures and expand upon the screens. The work for the Fellowship uses this wooden architectural structure reminiscent of large-scale mechanical loom. When you look at it, it looks like an interesting architectural, wooden structure but there’s a narrative that runs through it. I’m interested in trying to incorporate that more.

MS: That’s so beautiful, this narrative that is taking you into the future. A-M journal recently said you were an emerging artist in 2024 to watch out for and in the years to come. What does the term emerging mean to you?

RF: It’s a funny term because it’s also a very, loosely based definition because you can be an emerging artist for an extended period. It’s not age-related. I think it’s more of a self-identifier of where you are in your artistic career. I still consider myself emerging as I’ve only been practicing for a few years, not even four or five years now and at locations consistent with that stage. There are a lot of aspects within my work and practice that I’m still questioning and learning – I think maintaining that inquisitive nature within your art practice keeps it exciting, engaging and experimental, which is how I want to keep making into the future.

Check out more of Remy Faint’s work on Instagram at @remy.faint and https://remyfaint.com/